As a lover of classical music, I am sometimes reminded that, at the time much of the music I listen to was composed, there were only two ways for the public to hear it.

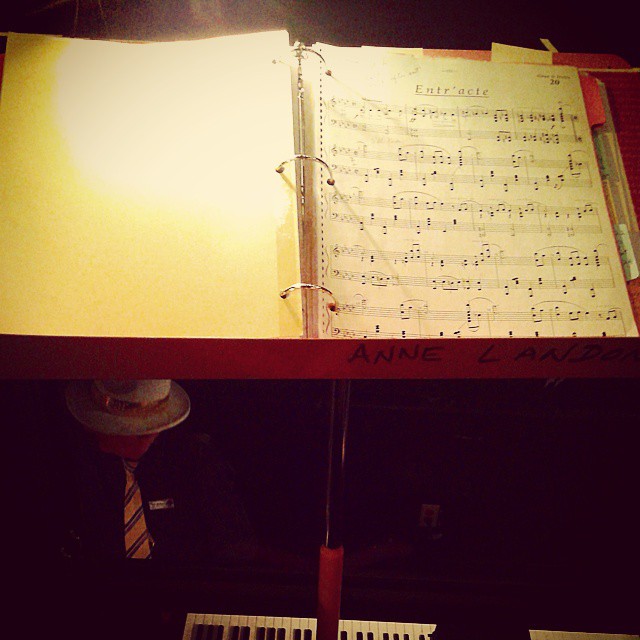

The first was for someone to purchase the sheet music and play it. This would have worked fine for single instrument pieces, provided the person in question had musical skill.

For the vast majority of the listening public, and certainly in the case of symphonic music, the only way to hear a piece was to attend a live performance.

I have a hard time wrapping my head around this idea, while my iPod plays Aaron Copland as I write these words.

But I find it even harder to imagine a future without live music.

This dystopian possibility, in which live musicians are replaced by pre-recorded music on a computer, is the endgame local musicians are worried about when they protest against St. Lawrence College's decision to use computerized tracks in their coming show, Legally Blonde.

There is at least one precedent for this scenario: the 2009 Brockville Operatic Society production of Singin' in the Rain, which drew widespread condemnation for replacing the pit with recordings.

The SLC production won't use such a sterile approach, but will rather use five live musicians alongside software tracks.

That's not quite the dystopian future yet, although Al Torrance, president of the Upper Canada Musicians Association, does raise another nightmare scenario: software errors, mid-show.

“You can see the Spinning Wheel of Death,” said Torrance, evoking an image that strikes immediate fear and rage in any Windows user.

“It can happen.”

There will be a great deal of schadenfreude if this actually happens during the show, though for the sake of the kids one does not wish it.

In fact, the ideal scenario is that Legally Blonde goes off without a hitch, so the truth can emerge more quickly.

And in showbiz, the moment of truth is nothing other than the audience's reaction. The ticket-holders also hold the entirety of the power in this equation.

So, if the public sees a discernible weakening of quality with the use of software-augmented music, the public will be left with two choices: either put up with it, or put up more money to demand more.

I take SLC campus dean Doug Roughton at his word when he says the music theatre performance program is finding it financially harder to put on such mega-productions as that glorious 2007 staging of Cats.

I note, for emphasis, that the date was 2007, a year before the most recent great recession not only tilted the playing field, but bombed it to rubble. Add to that the rapid rise, in the ensuing years, of easily accessible electronic entertainment and you have an increasing series of headaches for producers of traditional musical theatre.

(The scenario, incidentally, is not unlike the one that has left my newsroom a lonelier place.)

In this new economic reality, it just may be inescapable that big shows with full, human-only orchestras are a higher-end item, only available at a higher ticket price.

Staging them would be wonderful, but for the drawback that, just like symphony concerts, they will become the entertainment of the rich.

If, however, the public decides to put up with it, then it is also imperative the public draws some limits around what it will tolerate.

A return to the computer-only experiment of 2009 would be one of those things on my no-go list.

Another firm condition would have to be holding Roughton to his commitment to use local performers “whenever possible.”

“Whenever possible,” by the way, should mean “almost all of the time.”

A professional theatre company would be free to pick its musicians wherever it sees best, but SLC is not a professional theatre company. It is a post-secondary institution supported in part by taxpayer dollars and those taxpayers can, in this case, insist that whatever use of musicians remains supports the local economy.

For now, however, I am mentally preparing for what will likely be a tricky theatre review.