“You know, I wonder if we, as a city, can somehow sponsor several families... Remember, almost all of us are immigrants of this beautiful, fantastic and colossal country.”

That comment, from one of my Facebook friends yesterday on the subject of Syrian refugees, was another useful reminder that, while Facebook is stultifying ninety per cent of the time, it bears watching for that other ten per cent.

We have all by now seen that heart-wrenching image of three-year-old Aylan Kurdi's body washed up on a Turkish shore.

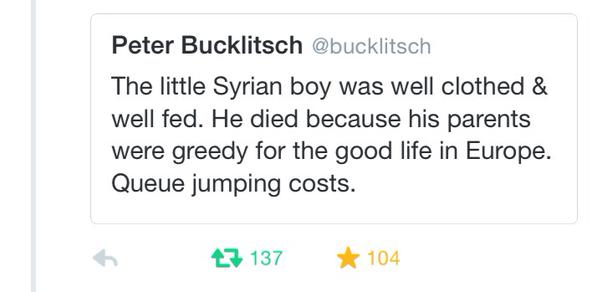

There remains, of course, a minority of the population that will always sickly cheer for the ocean in these tragic situations.

Thankfully, for the most part that image has been galvanizing public opinion in favour of doing more for Syrian refugees. It has even shaken up a Canadian election race that had seemed more or less complacent until now.

And when a public reaction driven by sympathy runs this deep, the question inevitably trickles down to the local level: What can we do to help?

That same very simple, very basic and very sincere question was what then Brockville mayor Ben TeKamp asked just over a decade ago, in January 2005, when he led a hastily-called meeting of community movers and shakers in the city council chamber to discuss the devastating South Asian tsunami.

So hastily was that meeting called that the agenda spelled it “Sunami,” but people showed up, including my publisher/boss at the time, radio host Bruce Wylie, the chamber of commerce and the Red Cross.

The purpose of the meeting was to discuss what the community could do to help people on the other side of the planet, following a gut-wrenching tragedy of another kind.

Plenty of local support flowed from that impulse, so much that for a while afterward The Recorder and Times printed a 'Relief Effort: What's On Here' segment.

I am not suggesting the same kind of locally organized response will happen to this humanitarian crisis.

For one thing, paying for a relief pack to be sent to a disaster-stricken community in Asia is several orders of magnitude cheaper than paying to sponsor a Syrian refugee family.

The latter is not accessible to your usual relief donor – nor is the ocean of bureaucracy that must be navigated to bring refugees here, which is another point of contention in the federal campaign.

Nevertheless, the staggering success of Canadian Aid for Chernobyl demonstrates that community-based charities can deliver large sums of money for humanitarian assistance. And Canada's response to the Vietnamese boat people crisis of the late 1970s and early 80s sets a precedent for this country opening its doors to people in need, people who have gone on to become productive members of Canadian society.

Once more, then, any local response to this international crisis will have to begin at the grassroots level, with churches, charities and other non-profit groups stepping forward convincingly enough to move public policy.

The city's role, perhaps, may be to help such people push all that goodwill through the gears of government.

None of this would solve the underlying problems causing this crisis. But if enough communities do it, it may shame nations into taking action.