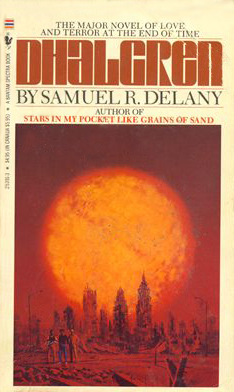

("Dhalgren-bantam-cover" copied from

Bantam Books website, and intellectual property

owned by Bantam Books.. Via Wikipedia)

Last week's "ghost game," the Major League matchup between the Chicago White Sox and Baltimore Orioles played at an empty Camden Yards, has been the subject of many dystopian comparisons already. Some are a bit too facile, like those Mad Max comparisons, and they all leave something missing.

There was an echo of something read and internalized long ago, something haunting, about the image of a city roiling with racial unrest all around the enclosed, denial-filled space of a major-league ballgame with no fans.

And then it came to me, as eerily and suddenly as the dysmetric disorientation of Bellona’s streets: Dhalgren.

If you have never read Samuel R. Delany’s 1975 masterpiece of genre-defying science fiction, I urge you to do so now.

This gigantic book follows a young, mentally ill drifter who has forgotten his name, and goes by Kid, Kidd or The Kid. He enters Bellona, a fictional Midwestern American city nearly emptied by some surreal, unspecified disaster that sometimes alters space and time. Amid the anarchy of Bellona's remaining inhabitants is an undercurrent of racial unrest.

Parts of this book will shock the uninitiate: explicit sex, both gay and straight, for starters, and, disturbingly, the hinted-at possibility that an African-American local folk hero might have raped a young white girl. But beyond that, the realization will soon dawn that, almost 40 years to the date after its publication, this Moebius strip of a book, written by the first African-American to break significantly into science fiction, has come back, in a different, more terrible form, as one aspect of American reality.

(To makes this temporal link even more eerie, this same book was referenced in the context of the unrest in New Orleans post-Katrina, during the last decade anniversary of its publication.)

There is too much to Dhalgren to cover in one blog post. Might I suggest, for instance, that Dhalgren’s distortions of reality – most significantly the two moons, the gigantic red sun and the buildings that burn perpetually without being consumed – might be apocalyptic representations of the social upheaval happening on the streets of its fictional Midwestern city? To the 2015 first-time reader, one almost senses Delany mocking the current-day conservative who sees the unrest in the streets of Ferguson, New York and Baltimore and exclaims: “The end is nigh!”

As I said, there is much to this book and it would be a grave disservice to confine it entirely to the subject of race. But race nonetheless plays a significant role in Dhalgren, and at the moment it is a racially-tinged segment of this gigantic tome that comes directly to mind.

The third chapter, “House of the Ax,” includes the racially ambiguous hero Kid’s interaction with the Richards family, a parody of the white middle class ideal of the age. The father, Arthur Richards, leaves dutifully for work every morning and returns every day, despite the lack of any working economy in anarchic Bellona and the obvious disasters in the environment. His wife, Mary, goes about keeping the house neat and hosting dinner, while children June and Bobby inject hints of darkness as they battle secretly over June’s obsession with George, the African-American who may have raped her.

Readers familiar with Dhalgren will remember the Richards family dinner scene, which goes on with an assiduous obliviousness to the disasters unfolding in the city surrounding it.

It is here, more than anywhere else, that one sees a haunting similarity with a major league baseball game going through the idiosyncratic motions of the sport, assiduously oblivious to the fact the city surrounding it is burning with anger and unsafe for fans. The Richards family strives to convince itself that all is normal and safe for its Cleaveresque existence, just as Baltimore strove to convince itself that it could play ball as the city roiled with anger.

It’s been said Dhalgren is a book with multiple entry points. This week, as Baltimore’s ghost game tried and ultimately failed to deny the reality around it, the House of the Ax links our reality with the apocalyptic world of Bellona.